Michelangelo images

below are presented under "Fair Use" doctrine, pending approval from

Museums

|

| Who, or What, was

Michelangelo looking at when he made this drawing? |

|

|

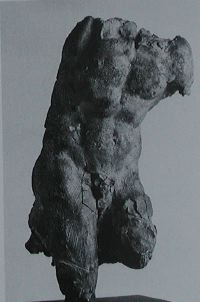

Model of a nude torso

clay

(later painted green)

c. 1520

|

|

Compositional Sketch for 'Judith

and Holofernes'

Black

chalk on paper

c. 1508

|

|

Studies of flayed arms

Pen

and brown ink on paper

(Red chalk drawings on the same sheet were likely made at a different

time, for a different project)

c. 1514

|

|

|

A group of three

nude men

Black

chalk on paper

c. 1504-5

|

|

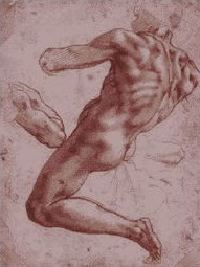

Study for a seated male nude

(Ignudo)

Red

chalk on paper

c. 1511

|

|

Study for Adam

Red chalk on paper

c. 1511

|

|

Realistic

"sculpture", these

clay hands

were made from plaster life-casts. An artist could draw these

clay hands so that they seem to be from a live model.

(to reference in text)

|

|

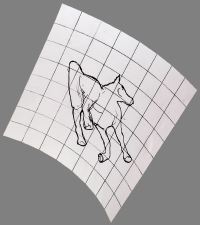

Enlarging

a figure with the correct perspective onto a curved surface is

trivial if one has a 3-dimensional model of the figure. Here

a

small plastic horse is suspended with string. A candle (right

side, lower corner)

provides a light source to cast a shadow on the curved surface

(upper left).

|

|

|

|

|

Tracing

of a shadow of the plastic horse on paper attached to

a model curved ceiling.

The curvature of the grid-lines shows the form of the model

ceiling. Rough interior

contours added free-hand after tracing shadow. Although the

"ceiling" is curved, the

figure appears in correct perspective when seen, as here, from the

intended viewing location.

|

|

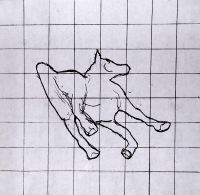

A red

chalk drawing of the plastic horse.

The silhouette of the horse was traced from a shadow

(onto a flat

sheet for this drawing), while inner contours, details, and

shading were drawn free-hand while observing the plastic model.

This

red chalk drawing captures a particular lighting of the model.

Certain parts of the figure are drawn to different scale, for

the

purpose of studying finer details. The drawing was completed in

about an hour. The detail in this regular 2-dimensional

drawing could be used to

fill in the detail for the distorted shadow outline above (right column). |

|

|

|

|

|

Drawing, Sculpture, and the Sistine Chapel

Ceiling

The traditional interpretation of

Michelangelo's figure studies is really only a guess

Analysis based

on research

at the 2005/6 Teylers Museum hosting of the Michelangelo

Drawings exhibition, and at the Vatican

(short summary here)

By Karl Zipser

12

March 2006

Michelangelo's

Lost Three-Dimensional "Sketches"

The historical Michelangelo

Drawings

exhibition (British Museum through 25 June) gives a

sense of seeing the artist at work, of watching masterpieces take shape

from the most

humble beginnings. This feeling is perhaps justified, because

drawing

was an essential tool for Michelangelo's preparation of larger

works. And yet, before jumping to conclusions about

what his drawings

tell us, it is critical to realize that there was another type of

preparatory "sketch" that Michelangelo used: his small

three-dimensional figure models. These

models are almost

entirely lost 1,

and it is easy to overlook their importance. But they

probably played as critical a role in Michelangelo's creative process

as drawing on paper. By ignoring how this class of work

relates to the drawings,

which the Michelangelo

Drawings exhibition for the most part does, it becomes

impossible to reach a

full understanding of how Michelangelo worked; it is difficult to say

with confidence what were the purposes, or even the subjects, of some

of his best drawings.

Any doubts about the importance of the preparatory model are dispelled

by Michelangelo's own words in one of his sonnets:

When

divine Art conceives a form or face,

She bids the craftsman for his first

essay

To shape a simple model in mere clay:

This is the earliest birth of Art's

embrace.

In

these lines Michelangelo describes forming a clay model as preparation

for carving a marble sculpture. His celebration of the humble

medium

of clay should not to be dismissed as poetic license, because he wrote

from his own experience. Michelangelo's clay models must have

been

remarkable sculptures in their own right; most likely they

rivaled the beauty of his drawings on paper. A clay model attribute to

Michelangelo is show in the left column.

Despite the survival of a few models of questionable authenticity, for

the most part the lost

clay models cannot speak to us or inform our understanding, unless we

can find some further trace of them. The

colossal marble sculpture

does not

easily reveal to the imagination its humble origins of clay 2.

But

where to search for the lost models? As I said

above, the Michelangelo

Drawings exhibition gives a sense of seeing the

master at work. If there is any real basis to this

impression, if the

drawings really do

provide a picture of how Michelangelo worked, then

the place to search for the lost clay models is in the drawings

themselves. Of course, the impression of "seeing the master

at work"

from the drawings might be an illusion. But as we shall see,

Michelangelo's drawings will not leave us disappointed in the quest to

rediscover the lost models.

Michelangelo's

Drawings and the Three Elements:

Imagination,

Reality,

and Style

Although

Michelangelo's finished masterpieces are impressive for their awesome

dimensions, he confronted his core creative challenges at a smaller

scale; the lines from the sonnet quoted above make this

clear. But reducing the scale of an artwork does not in

itself simplify the

complexity of its content. Even working on a small scale, an

ambitious

artist like Michelangelo had to confront a daunting challenge of

combining

three distinct elements: the freedom of his imagination, the

constraints of realistic form, and the interpretation of style.

While

the still-life painter or the abstract painter can in part escape these

challenges by abandoning imagination, in the first case, or the

constraints of depicting reality, in the second, Michelangelo

confronted the full challenge of bringing together these three elements

of art. And yet there is every indication that he

did so

not in a wild, reckless, or heroic manner; but rather, that he used a

systematic approach, divided his problems into parts, and created a

successful fusion using his deliberate preparations.

To see the

evidence of this in the Michelangelo

Drawings exhibition, we can look at 1) drawings which

are clearly made from imagination, 2) drawings that are

non-idealized studies of the living or dead human bodies, and 3)

drawings connected to the stylistic content of ancient sculpture.

Drawing

from

Imagination

A

rudimentary compositional sketch for the Judith and Holofernes

scene in the Sistine Chapel (see left column) contains little

sense of realism or

style. It

is a pure work of imagination, an early statement of what the final

fresco scene should contain. Perhaps it is nothing more than

a sort of

visual shopping list, making a record of what will be needed, with an

approximate location for each figure. It is not an especially

good drawing, but

it was probably in some way useful to Michelangelo, and to us it

provides valuable

information. We see that Michelangelo's artworks could grow

from the

most humble imaginary beginnings.

Drawings

of

Realistic Human Form

Some

of Michelangelo's least artistic drawings are those in which he seems

to

make a faithful record of what he saw. For example, he made

brown pen and ink drawings

of the arm muscles of a flayed corpse, diagrams full

of information,

but of little immediate aesthetic value [Studies of flayed arms,

(left column)].

Here we see Michelangelo collecting data on human form,

but not

idealizing or interpreting it immediately. The data is left

in a raw

form. This does not make for the most interesting picture,

but as a

faithful record, this anatomical data could serve him in later

work.

Another

example of Michelangelo working, apparently with an effort to record

realistic form, is in a drawing of two male heads [Two

heads, right column)].

The faces depicted here have a sense of realism, a prosaic quality of

everyday life. The faces are not idealized or heroic, they

are quite

unlike what we think of as Michelangelo's artistic vision of

man. And

yet, as faithful records, like the anatomical data, they could serve as

a basis for later work.

The drawings of realistic form not only

show a dispassionate side of the fiery-tempered Michelangelo.

They

also show him dividing his problem into parts literally, by using

separate

studies for different parts of the body.

Drawings

from Ancient

Sculpture

Michelangelo

made extensive drawing studies of ancient Roman marble

sculptures. It

is clear that he was interested in the poses of the figures, but

perhaps even

more in their style. Unfortunately, the Michelangelo Drawings

exhibition does

not

contain drawings of ancient sculpture that are obviously made directly

from sculpture itself, although such drawings exist. But

his

experimentation with drawing variations on the pose of the ancient Apollo

Belvedere sculpture [e.g., left column, A

group of three

nude men;

right column, A

youth beckoning] show evidence, within the

exhibition itself, of his

fascination with ancient sculpture pose and style. Here is

evidence of

the proud Michelangelo borrowing the ideas of other artists.

In

the drawings described above we have seen Michelangelo at work with the

three elements: the imaginary, the realistic, and the

stylistic. Although these are

perhaps mediocre

from an artistic standpoint, this does not detract from their

importance. These drawings show how Michelangelo studied each

of the

three

elements of art, to some degree in isolation, in much the same

way that he sometimes

studied different parts of the body in separate drawing

studies.

Michelangelo's great masterpieces did not arise in a single step, like

God's

creation of Adam as described in Genesis.

Rather, as the drawings discussed above show, he built,

or at least had the

option to build, his complex artistic world from the simplest

elements.

Bringing

the

Elements Together:

Drawings for the Sistine Chapel Ceiling Frescoes

Michelangelo's

great challenge, of course, was to combine the three elements,

imagination, reality, and style. The fact that he studied

each in

isolation (too some degree) implies that when he wished to bring these

elements together,

he could do so using the results of his separate studies, using his own

drawings as data. When he brought

these

elements together in drawing, he produced rich artworks; but these

drawings are inherently more difficult to classify into the elementary

categories that have been discussed above.

Perhaps the most beautiful and

ambiguous of Michelangelo's surviving drawings are his magnificent red

chalk works for the Sistine Chapel ceiling, listed below:

Study for

a seated male nude (left column)

Study for

Adam (left column)

Studies

for Haman (right column)

Studies

for the Crucifixion of Haman (right column)

I will refer to these as "the red chalk drawings". These

drawings have the following in common:

1) each

contains a remarkable representation of male human form;

2) each is closely related to the appearance of the figures in the

ceiling frescoes;

3) each is a highly refined drawing with rich anatomical detail;

4) each shows an incomplete figure, with the representation of the body

divided into parts, not necessarily consistent in scale;

5)

the poses are heroic in character, poses which would be

uncomfortable, or impossible, for a live model to maintain for a

sustained length of time;

6) the figures do not look like ordinary

people, but like ideal human forms, with style clearly related to, but

still distinct from, ancient Greek and Roman sculpture.

Together

these common qualities point to the drawings not being merely pure

works of imagination, studies from reality, or quotations from ancient

sculpture. Rather, their common qualities show that the

drawings are a

synthesis combing all three elements. How then should we

answer the

simplest of questions: who, or what,

were the subjects for these

drawings?

The Michelangelo Drawings

exhibition provides a definitive answer -- these red chalk drawings are

studies of live human

models. This is stated as a "fact" by British Museum drawings

curator Hugo Chapman 3

in the volume that accompanies the exhibition. Although

the makers of the exhibition recognize that Michelangelo has

brought together the three distinct artistic elements in these

drawings, they fail to follow the line of reasoning to the logical

conclusion.

How can the exhibition be so certain that Michelangelo drew these

figures from life?

Is it not equally likely that these magnificent drawings are in fact

depictions of small clay models? 4

The

functional connection between 3-dimensional and 2-dimensional

artworks

Although

he does not mention it in the sonnet quoted above, we know that

Michelangelo used drawing as an aide in making sculpture.

That is to

say, Michelangelo used 2-dimensional drawings, such as the remarkable

studies for the figure of 'Day' to

guide in the creation of 3-dimensional

physical form. But conversely, sculpture has been equally

valuable

for making drawings; that is to say, using the 3-dimensional to create

the 2-dimensional. We have already seen one aspect of this in

Michelangelo's use of ancient sculpture. But drawing from

ancient

sculpture has the inherent limitation that one must accept the

3-dimensional sculpture as one finds it.

Another approach, which gives more

flexibility to the artist, is described by Cennino Cennini in his "Il

Libra dell'Arte", written perhaps in the 1390's. After

describing

drawing and painting techniques in great detail, Cennini in the final

section of his book writes "I will tell you about something else which

is

very useful and gets you great reputation in drawing, for copying and

imitating things from nature: and it is called casting." 5

Cennini

proceeds to explain how to make life-casts of human faces and complete

figures, using plaster of Paris.

Life-casting

is a simple way to

make realistic sculpture

(left column). Cennini makes it clear that an

artist,

without possessing the skills of a sculptor, can create life-like

three-dimensional forms; these forms he can draw or paint at his

leisure to create a result that seems to have been made from life,

without the disadvantages of working from a restless human

model. The

implications of Cennini's writing are profound. They suggest

that

whenever we see any portrait or figure in an old painting or drawing,

we must consider the possibility that we are in fact looking at an

image of a life-cast, not a living person. This was perhaps

standard practice.

Of course,

life-casting also has limitations. The artist can only make a

life-cast from a real person, and must accept the person as he finds

him. The life-cast will be life-sized, and thus unwieldy and

heavy.

But if the artist possesses the skills of the sculptor, he

can

make his

own life-like forms to draw. Michelangelo, one of the

greatest

sculptors and draftsmen of all time, had a unique opportunity to create

life-like models, and to draw them so that they looked alive.

This I

propose is precisely what he did with the Sistine Chapel red chalk

drawings listed above. These drawings thus could rescue from

oblivion

some of Michelangelo's lost 3-dimensional "sketches". If we take

another look at the clay torso model show earlier with more dramatic lighting (right

column)

we can see how inviting a subject for drawing these models could have

been. Whether this particular model is an authentic

Michelangelo

is to some degree irrelevant; we only need to look at it as an example

of what Michelangelo could have made, and could have drawn.

Although

there is not any question that Michelangelo could have done

this, it

would seem to represent extra work in the context of a project like

frescoing the Sistine Chapel. From Michelangelo's drawings it

is clear

that he was not prone to do extra or unnecessary labor. For

example,

in a refined drawing of a figure, he would typically leave a hand or

arm in rough schematic form, if he knew that these body parts

would be invisible in the finished artwork. Thus, to support

my

interpretation, it is necessary for me to describe some very solid

advantages that Michelangelo would receive from the labor of making

clay models for his figures.

Purposes

for making 3-dimensional models, when a 2-dimensional image is

the goal

There are three distinct reasons for creating clay models for the

Sistine chapel figures.

The

first reason relates to the three elements of art that we discussed

above. If Michelangelo made a design from his imagination, if

he had

realistic life-studies of human models to serve as data, and if

he had a deep understanding of ancient sculptural style, he nonetheless

still had a huge challenge to combine these three elements.

The Michelangelo

Drawings exhibition, by proposing that the red chalk

drawings are life studies,

puts the enormous burden on Michelangelo of combining the three

elements while looking at a live model, a figure most likely not of the

ideal form that he desired for his artwork. But if instead

Michelangelo integrated the three elements into a clay model, as I

propose, he could work at leisure to create precisely the ideal human

form

that he desired -- in much the same way we know he did when preparing

to carve a marble sculpture 6. If Michelangelo's live

model for

Adam were an old man with pot-belly, he could nonetheless transform

that

figure into an ideal form in clay 7.

He could copy a head

from an

ancient sculpture if the live model's head did not satisfy.

In

sum, the

clay model presents the ideal medium for Michelangelo to bring together

the three elements, imagination, reality, and style. To do so

while drawing a figure from life is

possible, but it would be far more difficult, unless the figure already

had something approaching the ideal form.

The second reason the clay models would be

useful is because of their rigid physical stability.

Michelangelo was

interested in

depicting the most heroic and difficult poses. By making

clay

models, he could turn life

into still-life,

and draw at leisure -- just

as Cennini describes with the life-casts. Drawing from the

clay is the optimal

condition for making drawings as refined as the red chalk

drawings.

Attempting to produce a refined result when drawing a live model, a

person perhaps trembling from the strain of the pose, would be far

more

difficult and frustrating.

As the first two reasons make

clear, creating clay models, which might at first seem like extra work,

would in fact ease Michelangelo's creative

burden. For

these

two reasons alone, my interpretation of the red chalk drawings, as

depictions of clay models rather than live models, is

justified. For these two reasons, we can be skeptical of the

exhibition's certain claim that these are life studies. As we

shall now see, the third reason for making the clay sculptures is that

they allow for a simple solution to one of the most difficult aspects

of the fresco project: getting the figures onto the Sistine Chapel

ceiling.

The

Most Important Advantage of Using 3-Dimensional Models in Creating

the Ceiling Frescoes

Candlelight

in the Chapel

Whether

Michelangelo's drawings are from life or from clay models, the artist

faced a number of problems in putting them on the Sistine Chapel

ceiling. For one thing, he would have to enlarge

them. Normally when

artists enlarged a drawing, they drew a system of square grids on their

drawing, then drew a larger system of grids on the surface to be

painted, such as a panel, a canvas, or a wall. They could

then enlarge

the drawing by comparing the grids. This type of

enlargement is

so simple that it could safely be left to assistants.

However, there

are no such grids on the surviving drawings for the

Sistine Chapel ceiling. At first this might seem

mysterious. However,

there is a good reason that there are no grids on the drawings: grid

enlargement would not have helped

Michelangelo to transfer his drawings to the ceiling 8.

The reason that grid enlargement would

have been of no help is that the Sistine chapel ceiling is not a flat

surface; rather, it consists of many curving

surfaces. The

grid

method would not give the correct perspective for enlarging the figures

from normal drawings

onto these curved surfaces. To transform a flat drawing onto

a curved

surface, but retain the correct perspective and foreshortening of the

figures, represents a major computational headache. The task

is

complex because it is necessary to take into consideration both the

curvature of the wall and

the physical structure of the figure in the

drawing. For example, there are places in the Chapel where

the wall

curves forward,

but the figure leans backward;

both factors need to be

taken into consideration to produce the correct perspective.

Today we could use a computer for the task. To do it without

a

computer would

require extensive computation by hand, no evidence of which

exists.

How did Michelangelo do it then? The solution may be

this: although

it is difficult to enlarge a drawing,

such as that of the foreshortened

figure Haman, onto a curving ceiling, if, on the other hand, one has a three-dimensional model

of the figure, the process becomes

trivial.

All that is necessary is to arrange the figure in the correct pose

(perhaps suspending it with string, or supporting it with rods), and

then

use a candle to cast a shadow of the clay model onto the curving

ceiling. The enlargement and the

correction for the curvature

happen

automatically (see examples in left

and right

columns). With a computer today we could

simulate this

process with a virtual model of the figure, the wall, and the candle,

if no real three-dimensional model were available.

We

see then that Michelangelo would have a major incentive to create clay

models of his figures, in

order to get them onto the ceiling in the correct perspective -- if he

discovered the shadow projection technique.

It

could be objected that the sheer scale of the Sistine chapel, combined

with the particular structure of the scaffold used by Michelangelo to

reach the ceiling, might make it impossible to project clay models onto

the ceiling as I describe. This technical objection might

very well be

valid.

It all depends on the size of the clay models, the nature and strength

of the light source, and the exact structure of the scaffold.

However,

this technical objection is in no way

fatal to my argument. If

Michelangelo were for technical

reasons unable

to implement this scheme in the chapel itself, he could have achieved

the same result by projecting the shadows of clay models onto a simple model of the

Sistine Chapel ceiling 9.

Enlarging these

projections to the

chapel

itself would be a trivial matter of increasing the scale; the simple

grid

method would work (see examples in left

and right columns).

I have given three reasons for making the clay

models. Michelangelo might have initially made them for only

the first

two reasons. Having the clay models on the scaffold, he might

have

observed the effects of shadow enlargement by accident. But

with the

clay models ready, he could easily take advantage of the discovery.

Of

course the candle projection would give a result that was perfect for

only one viewpoint (in this case at the position of the

candle). But this

is a general limitation of

all perspective projections, for paintings on flat as well as curved

surfaces. Whatever method Michelangelo

used,

it would always

have this

drawback. This is inherent limitation of representing

3-dimensional

form or a 2-dimensional surface, whether flat or curved.

From

Shadow to Fresco

The

method of casting a shadow on the chapel ceiling (or a model ceiling)

would give the outline, or

silhouette of the clay model, but not any of the other internal

features -- in the same way that our own shadows delineate our outer

contours, but not our eyes or mouths (except of course when the

shadows are perfect profiles). In order to paint the frescoes,

Michelangelo would, of course, need more than the simple outline of the

figures. The task of adding features to the projected

silhouettes is

relatively straight-forward, because the artist can use the outer

counters as guides for where the internal features should be.

Michelangelo could refer to the

clay

models directly, or drawings of them, when adding the features to the

projected drawing.

A red chalk study of the horse

(left column) would likewise enable us to fill in the details for a

fresco cartoon.

Earlier

it seemed necessary to justify why Michelangelo would have made clay

models of figures such as Haman. But at this point we could

ask a

different question. If he had the clay models, why should

Michelangelo

have made the refined red-chalk drawings of them? The fact

that these

drawings exist does not in itself explain their purpose. If

Michelangelo

made

clay models, as I described, and if he used them to project the outline

of the figures on the ceiling, he could have also referred to the

models themselves to add the other details to the projected

image. The

red-chalk drawings would thus seem to be unnecessary. Thus,

in a sense

we have come full circle in the argument.

We see now that the

refined nature of the red chalk drawings poses a difficulty for the

clay model shadow projection idea. If Michelangelo had the

clay models, it

seems that

the refined drawings would be unnecessary. But since the

refined red

chalk drawings exist, we must show how they would still be essential to

the project, along with the proposed clay models. If we

cannot do

this, then we

are forced to assume that Michelangelo made these refined red chalk

drawings for no particular reason. Since this would be

absurd, it

would cast doubt on the clay model idea.

The solution to this dilemma is simple, however. Although

Michelangelo could have used clay

models

to transfer line

drawings of his figures to the ceiling (by tracing the

shadow, and adding interior contours referring to the model), he still

needed to paint the frescoed figures with the appropriate light and shade.

Theoretically, he could have painted from the models

directly. However, there is a problem in doing

this. The lighting

in the Chapel by

which he worked in painting the frescoes would likely not be the same

as

the lighting he wanted for his clay figures. Moreover,

because the

frescoes are large, he would have to move the clay figures around as he

changed position, in order to always view them from the correct

angle.

An easier solution than painting the frescoes directly from clay models

would be to make refined

shading studies of the clay

figures, using the correct lighting, and then to refer to these as he

painted. This, I believe, is the purpose of the refined

red chalk drawings in the Michelangelo

Drawings exhibition, such as that of Adam, Haman, and the Ignudo.

Thus, the red chalk drawings still have a fundamental role to play in

the making the frescoes, even if Michelangelo made clay

figures. A

drawing has advantages

that a clay model lacks, as a reference for painting: portability,

invariance over different

lighting conditions, and constant viewing angle of the figure.

Previously it was assumed that

the

refined red chalk drawings in the Michelangelo

Drawings exhibition are an early stage of the project --

something from which full-scale, refined cartoons could be

made. With

my interpretation, the cartoons -- that is, full scale drawings to be

attached to the ceiling itself to allow the drawing to be transferred

to

the wet plaster -- would need be no more than minimalistic outlines and

interior contours. The refined red chalk drawings we see in

the exhibition could be a

primary source for the fresco painting detail. This is

an

attractive idea, because it explains why the drawing are executed with

such refinement. It is also an exciting idea because it puts

the drawings

we see much closer to the final result: Michelangelo might have even

held these drawings in his hand as he painted.

The fact that

the

drawings are incomplete -- missing heads or arms -- is of no

importance. Michelangelo would have had these pieces on

separate

sheets, or even on the same sheets, as was his habit. To

paint the

head from one page, the body from another, would present no

inconvenience, given that a complete outline and major interior

contours had been transferred from the cartoon to the wet

plaster.

In fact, dividing the figures into separate parts would make it be

easier to use them, because the heads could be made in larger sizes in

the drawing to show better detail.

No full-sized fresco

cartoons for the Sistine Chapel ceiling have survived. Vasari

suggests that Michelangelo burned the cartoons. Perhaps this

was

not as absurd as it sounds

-- if the fresco cartoons were indeed as minimalistic as I suggest, and

that the best

drawing work was confined to the small (red chalk) drawings, some of

which still exist and are on display in the exhibition.

Conclusion

We

began with a search for traces of Michelangelo's lost 3-dimensional

sketches. We found what could be careful depictions of some

of them in

the red chalk drawings for the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

During

the difficult years of creating the ceiling frescoes, the artist

signed his letters to his family with the title, "Michelangelo,

Sculptor in Rome." During this time he was not able

to

create the marble sculpture that was his passion, and it is easy

to regard this title "Sculptor" as more wishful thinking than as

directly connected to his activities from 1509 to

1513. And

yet, as we have seen

in this essay, the designation "Sculptor in Rome" could have been

literally true during the fresco project. Michelangelo may

have formed

clay models of his figures, and used them to transform his ideas onto

wet plaster. If we take Michelangelo at his word and consider

this

possibility, we are able to reinterpret the entire process of creation

of the ceiling frescoes of the Sistine Chapel.

|

Notes

1

A small collection of model figures was found in the Casa

Buonarroti

in Florence. There is some mystery surrounding their origin.

Other figure

models elsewhere have been attributed to Michelangelo as well, but

authenticity is generally a matter of controversy. The site Michelangelo's Models discusses these models in detail.

2

Michelangelo also modeled with wax, and perhaps other media.

Giorgio Vasari, Michelangelo's friend and biographer, records that the

sculptor carved the colossal marble 'David' from a small wax

model.

Clay is the more plastic and sensuous medium, whereas the wax model is

less fragile. Although I refer to clay models in this essay,

wax could

fulfill the same role.

3 "As

with the earlier Cascina figure studies, the fact that

Michelangelo was drawing from a model did not prevent him from

adjusting the forms for artistic effect." See Hugo Chapman's Michelangelo Drawings: Closer to

the Master, p. 129

4

The makers of the Michelangelo

Drawings exhibition are of course not

ignorant of the possibility that Michelangelo could draw from small

model figures. But they use this concept to reach an odd

conclusion. With reference to the fact that the drawing

technique for A

flying angel and other studies is crude and mechanical,

they

suggest that this may be a result of Michelangelo drawing from a small

model figure. Given Michelangelo's talents in sculpture and

drawing,

this argument is inexplicable; it is as if to

suggest

that Michelangelo would have found his own sculptural models

uninspiring subjects. In another essay I give a different

explanation for the quality of the

drawing in question, namely, that it may be a forgery.

5 Quoted

from Daniel Thompson's translation, The

Craftsman's Handbook. Cennini believed that

life-casting was

also the

basis of sculpture in ancient times, from which, he says "many good

figures and nudes are to be found." In light of the ancient

Roman

marbles that would be unearthed after Il Libro dell'Arte

was

written, Cennini's statement about "many good figures" is indeed

prescient.

6 The

only important difference is

that the

clay models for the Sistine Chapel would require less work, because

unlike the case of marble sculpture, the figures in the frescoes can

only be seen from a fixed viewpoint, not from any side.

Michelangelo

would not need to worry about the muscles of Adam's back, or the chest

of the Ignudo depicted from behind. In

other

words, making the clay models for the Sistine chapel would have been

familiar work to Michelangelo, but less demanding than what he was used

to in his usual work as a sculptor.

7 Michelangelo

was the master of

transformation from the real to the ideal. For example, in

what is

apparently a non-idealized life-study for a figure in the Sistine

Chapel ceiling frescoes [a drawing not in the Exhibition],

Michelangelo depicted "an elderly man with a slight paunch and sagging

buttocks. " Michelangelo somehow transformed this ordinary

man into

one of his heroic, gargantuan fresco figures; furthermore, in the

chapel, the figure is a woman. [See Michelangelo and the Pope's

Ceiling, by

Ross King].

8 Hugo

Chapman writes, "There are no known examples of Michelangelo squaring

his preparatory drawings so one can only assume that he copied them

freehand." p. 120. This freehand copying and enlarging of the

figures would be a huge amount of work, and very difficult because of

the curvature of the ceiling. As I explain, there is a much

simpler alternative.

9 A

model of

the Sistine chapel ceiling would have been of great help to

Michelangelo, whatever method he used to transfer his drawings to the

ceiling.

With the real

ceiling,

the artist standing on the scaffold sees a highly distorted view of his

work; the spectator standing far below on the chapel floor sees the work in

the correct perspective (if the scaffold does not block his view).

With a small

scale model of the ceiling, the artist can see his work in

correct perspective, and also

work at the same time.

To enlarge the design from the model ceiling to the full-scale ceiling

is trivial. Thus, working with a model ceiling offers an

advantage

in preparing designs for the ceiling frescoes, because the artist can

deal with the problem of the curved ceiling while working, and enlarge

the scale later.

Furthermore,

if Michelangelo had a small model of the ceiling with which to work, he

could position himself in the intended viewing position for the fresco

and draw at the same time. Working in the real chapel,

Michelangelo

could not stand in the intended view-point at the same time he

worked.

When seen from the intended viewpoint, the figures on the fresco would

not seem distorted by the curvature of the wall, by

definition. Thus,

drawing from this position is easy. However, from other

viewpoints,

particularly the extremely close viewpoint necessary to paint the

actual frescoes, the distortion of the figures would be extreme.

The

fact that the Sistine Chapel ceiling consists of a

small

number

of repeating elements means that a small set of simple models of the

ceiling would suffice. There would be no need to construct a

model of

the complete chapel ceiling. The model ceiling segments could

have

easily been constructed from wood.

Michelangelo was famous for working in secrecy. The technique

of

shadow projection I discuss is so simple and rapid that, if he used it,

he could easily have hidden the technique from his own assistants. |

|

References

Cennini, Cennino. Il

Libro dell'Arte. The Craftsman's Handbook.

Trans. Daniel V. Thompson. New Haven: Yale

University Press, 1933.

Chapman, Hugo.

Michelangelo Drawings: Closer to the Master.

London: The British Museum Press, 2005.

King, Ross. The Pope's Ceiling.

New York: Penguin Group, 2003.

Vasari, Giorgio. Lives

of the Painters, Sculptors, and Architects.

Trans. Gaston du C. de Vere. 2 vols. London:

Everyman's Library, 1996

|

|

| Text

and non-Michelangelo images © Copyright Karl Zipser 2006, all

rights reserved. |

Essay List

Karl Zipser's Homepage

|

|

|

Two Heads

Black

chalk on paper

c. 1534-36

|

|

A youth beckoning

Pen

and brown ink on paper

c. 1504-5

|

|

|

Studies for Haman

Red chalk on paper

c. 1511-1512

|

|

Studies for the Crucifixion of

Haman

(monochrome reproduction)

Red chalk on paper

c. 1511-1512

|

|

Model of a nude torso

clay

c. 1520

|

|

|

|

Closer

view of shadow projection. The shadow appears

distorted from this view, but from the position of the candle, the

shadow silhouette has the correct perspective.

|

|

The

shadow projection drawing detached

from model "ceiling" and laid flat. In this geometry,

the

figure is distorted, the grid-lines straight. The grid makes

it

trivial to enlarge this (intentionally) distorted image to a

full-sized fresco cartoon to be attached to the real ceiling.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|